The 4 Chapters

Don’t Monkey Around With Sin Like Enoch Emory

By Contributing Author, Robert Shashy

Welcome to the first installment of The 4 Chapters. My name is Robert Shashy, and I am a seminary student and aspiring Church leader. It is my goal that these articles will help connect literature, film, and various other cultural happenings with Christian living and doctrine for the 21st Century American Christian. Thank you for taking the time to read what I felt like writing; may it be edifying to you, and glorifying to the Lord, Jesus Christ.

It is currently the middle of October, and I am finally enjoying a much-needed break from my seminary coursework. Coupled with my mini-sabbatical of sorts is the change of seasons from Summer to Autumn. With this change has come cooler weather, even for us Floridians, and thus a change of wardrobe. I have had more time to enjoy the small daily tasks like going to the store. And this year, I’ve noticed less of an interest on Halloween than in past years. I’ll admit, I want to like the spooky season, but, putting aside any question of whether Christians should engage with the horror genre, my imagination is too active for me to read or watch the scarier stuff. Still, each October I try to read through The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor.

Flannery O’Connor probably doesn’t need much of an introduction, but I’ve also found that many people just find her boring. As a fan of Southern Gothic literature, and as a Christian, her stories resonate with me. Ms. O’Connor is credited with saying that America, especially the South, was “Christ-haunted,” in her time. And indeed, many of her stories build up to crescendo in scenes that still perturb me days, weeks, and years after I first read them. Such is the case with the story I want to talk about today: Enoch and the Gorilla.

A Peeler, A Park, and a Boy’s New Outfit

In Flannery O’Connor’s collected stories, the character of Enoch Emory appears in three separate narratives. First in a story called The Peeler, where Enoch is not the main character, but being new in town, he is desperate for friendship. He seeks that companionship from the main character, Hazel Motes, but to no avail. We see Enoch run off crying at the end of the story. The second time we see Enoch is in The Heart of the Park. In this story we learn more about his job working for the local zoo, and see that in his free time he awkwardly watches people swim, or flirts with woman working at the local diner. Enoch’s awkward loneliness becomes clearer, despite reconnecting with Hazel Motes between stories. But even that connection seems to be because Hazel wants something from Enoch. And indeed, isolation is a theme throughout O’Connor’s stories. For as relevant as that theme was in the mid-20th century, it’s likely more relevant today. And that is where we find Enoch as we begin Enoch and the Gorilla.

Towards the beginning of the story, Enoch is alone and picking at an old umbrella his landlady let him borrow. Walking through town, he finds his way to the local cinema where it is being advertised that Gonga, a gorilla and movie star, will be greeting children. Keep in mind, Enoch is 18 years old in this story. None the less, the reader gets the sense that Enoch’s excitement will be for not. O’Connor writes “Enoch was usually thinking of something else at the moment that Fate began drawing back her leg to kick him.” She then goes on to describe how he chipped his front teeth as a young child, because his dad bought him an old-timey snake in a can. From early in the story, it is clear Enoch is not a character meant to encourage, or one to idolize, but one that should be pitied or mourned over.

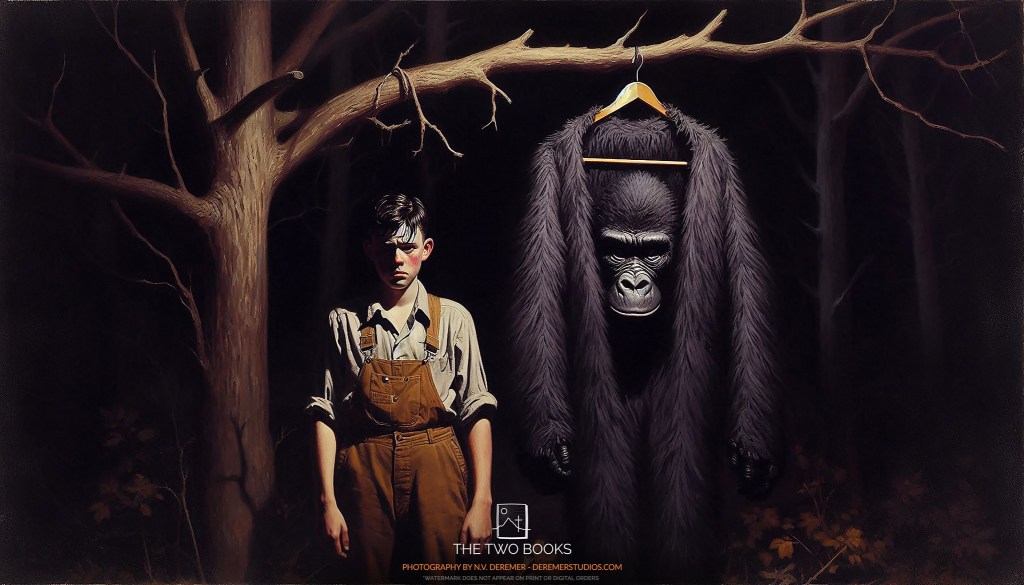

Having learned about the primate star’s meet and greet, Enoch gets in line with the children, but with a cruel intention. He wants to insult the gorilla to his face. Yet, as the gorilla makes his way to the crowd, Enoch finds himself as frightened as some of the children, if not more so. Flannery describes the gorilla’s growls as poisonous. Still, Enoch musters up the courage to shake hands, only to stumble over his words in the process of introducing himself. He then realizes that Gonga is not a real gorilla, but a man in a suit. In an ironic turn, this man insults Enoch, telling him to “go to hell.” In a figurative sense, that is what Enoch does.

Flannery O’Connor’s literary technique throughout the story is striking. From the quip about fate, and the description of the poisonous growls, to returning to the umbrella Enoch was picking at until she describes it as being denuded. She hints at Enoch’s final destination throughout the story. In the second act, Enoch decides he will have his revenge, and is happy with this—but it never brings him true joy. He spends his afternoon flirting with another waitress who does not like him, reading the funny pages of the newspaper, and eating cake for dinner. If Enoch is anything but awkward and lonely, it is immature. Still, he sees his plan to fruition. He goes to the Victory theater, and sneaks into a van advertising for faux Gorilla star. When the van takes off down the road, that is the last we see of Enoch Emory. There is a tussle as the van drives down the road, and out emerges a figure beaten and bruised. A figure who himself disrobes, and buries his clothes—his former self. Then we see a figure that is black and white, that for a moment has two heads, but becoming one figure lets out the same poisonous growls mentioned earlier in the story. Enoch Emory is no more, he has given into his sinful desires, and become the gorilla. As the story crescendos and comes to its resolution, this gorilla man tries to greet a couple sitting beside the highway on a date. But he is too horrifying, and they both flee from him, just as Enoch should have fled from sin.

The Glory of the King, Not the Kong

“12 The night is almost gone, and the day is near. Therefore let us lay aside the deeds of darkness and put on the armor of light. 13 Let us behave properly as in the day, not in carousing and drunkenness, not in sexual promiscuity and sensuality, not in strife and jealousy. 14 But put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh in regard to its lusts.”

Romans 13:12-14, NASB1995

Like all of us, Enoch Emory had his own problems in life. He was awkward, lonely, and at times impulsive and emotional. But the solution was not for him to run to his sins, but to run to Christ. Enoch knew this too, as do many of Flannery O’Connor’s characters. Multiple time, Enoch mentions how he went to a Christian boy’s school when he was younger. Jesus has compassion for the lonely (1 Peter 5:6-8). He cares so much for His people, that He, too put on a suit – but for redemptive, not reprobate purposes by putting on our frail human flesh and becoming man (John 1:14-18, Phil 2:5-11, Heb. 2:17-18, and Heb. 4:14-16). In Enoch Emory we have the antithesis of a Christ-figure. Where Enoch is lonely and seeking community, Christ left the glories and communion of heaven for the loneliness of life on earth; where Enoch is awkward but thinks much of himself, Jesus left the perfect unity of the Trinity for the cold betrayal of His closest friends, and where Enoch rashly sheds his humanity to put on the form of a beast, Jesus purposely came down from heaven that He would shed His blood as a propitiation of His people’s sins (Rom. 3:24-25, 1 John 2:1-2). Enoch Emory’s story reminds us that as tempting as our sins may seem, they ultimately entrap us, and confirm us into the image of something untamed and hideous, something far from Christ.

“5 Have this attitude in yourselves which was also in Christ Jesus, 6 who, although He existed in the form of God, did not regard equality with God a thing to be grasped, 7 but emptied Himself, taking the form of a bond-servant, and being made in the likeness of men. 8 Being found in appearance as a man, He humbled Himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross. 9 For this reason also, God highly exalted Him, and bestowed on Him the name which is above every name, 10 so that at the name of Jesus every knee will bow, of those who are in heaven and on earth and under the earth, 11 and that every tongue will confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.”

Philippians 2:5-11, NASB1995

At the same time, Enoch reminds us that we are made for community, and that isolation is a product of the Fall. That isn’t where the story ends though. Enoch’s immaturity was not just a matter of the years of his life, but the quality of his relationship with Christ. The Bible warns us about this latter immaturity (Eph. 4:14-16, 1 Cor. 2:14-16), and points us to Christ. It is in Christ that we find the happy ending to the story. It is in Christ that we find hope for healing and unity again, a hope that points us to the reality that will be when Christ returns. But what do we do while we wait? Don’t monkey around with sin like Enoch Emory; don’t put on that monkey suit. Instead, just as Christ put on the flesh for you, put on the new self in Christ. Put sin to death, and walk in the path Christ has made for you (Col. 3:9-10). Read the Bible, be committed to the community of the local Church, and be trained up in all ways to put sin to death (Eph. 4:21-24).

Before concluding, it is worth mentioning that the three stories discussed in this article: The Peeler, The Heart of the Park, and Enoch and the Gorilla were eventually re-worked by Flannery O’Connor to be chapters of her novel Wise Blood. In particular, chapter 11 reworks the story that has been the focus on this article, but it doesn’t have the same lingering quality of the author’s shorter work. Many of her stories leave the reader contemplating the idea that America—even in the 21st Century—is haunted by Christ. If you are looking for additional reading suggestions this month, consider The River, Good Country People, A View of the Woods, or Parker’s Back. And as the weather continues to chill, and you contemplate what you will wear to stay warm, don’t dress yourself in some wild outfit that will enslave you in base desire, but rejoice in garments of salvation that God has prepared for you in Christ (Is. 61:10).

About the Author

Robert was born and raised in Jacksonville, Florida as a Roman Catholic. While at the University of Florida, he became a Reformed Evangelical after joining Reformed University Fellowship (RUF). He still remains compassionate towards Roman Catholics, and sees reformed Catholicity as key to Church, both in America and globally. He currently is a seminary student at Reformed Theological Seminary Orlando, and an aspiring pastor. Feeling called by Jesus to contextualize the culture to better share the Gospel in the 21st century, Robert feels called to help lead the de-churched back to Christ, and help Christians better understand both who the Bible calls them to be, what society around them has to say, and how to best follow Christ’s lead in this life. Robert looks forward to a day when the American Church better resembles the safehouse and hospital it is supposed to be (1 Peter 2).

Leave a comment